In my first CEO role, I did not know anything about the job, but I had held several diverse executive roles, and I had worked for a couple of great CEOs, so basically, I thought I was good to go. I was so excited to have the opportunity to become a CEO that I skipped all of the diligence steps, and essentially said yes before they even offered the job. I never even questioned why they would consider me for the job when there were tons of better qualified people out there. I quickly learned a few important lessons that have guided me through all of my subsequent CEO roles.

The first thing I learned was the difference between a restart and a startup. I was hired into a restart, and that was very different from what I naively expected. The best analogy to understand the difference is building a house. A startup is like building a house on a vacant lot. It is a creative project that can go in any direction. A restart is like buying a lot with a broken down house already on it, with all sorts of zoning rules that require you to rebuild within the existing footprint, and most of the systems need repair or replacement. You have to clear the rubble off the lot before you can begin construction, and you have to decide what if anything from the prior structure can be salvaged. A restart has a team of existing people who have already adopted policies and practices and habits. There is typically an installed base of customers, and usually an outdated product with technology debt. Most importantly, a restart already has a burn rate with licenses and leases, and maybe debt and covenants you cannot turn off.

Boards of directors rarely hire a new CEO unless the company really needs one, so chances are, if you are being considered for the CEO position at an existing company, you are probably walking into a restart or a pivot. Restarts and pivots happen with companies of all sizes, so do not assume that the company is on the right path just because it is established and has some scale. As a candidate, you need to have your senses on high-alert to make sure you fully understand what you will be dealing with. Having stepped into the role a number of times, I speak from experience when I say it is important to take the time to do your diligence and make sure you truly understand the reasons why the company is changing CEOs. When you ask board members why, do not blindly accept the first answer offered, even if it is totally logical and believable. Like a child, keep probing with ‘why’ questions.

An incoming CEO to a restart has to quickly learn the contours of what exists, and determine what can be preserved or enhanced, versus what has to change or be eliminated. You have to assess the existing team, and regardless of job title, you need to figure out who are the leaders and who may be the roadblocks, or worse, who are the trouble makers. A restart adds an entire new dimension to the challenge of achieving success.

In my first hired-CEO gig, the company had some fresh capital, but it was burning cash without a clear path to profitability. There was a lot to figure out. My first thought was to preserve the cash and do as much as I could with the people that were already in the company. Fortunately, a gray-haired wise board member took me aside and strongly suggested I hire an experienced executive team. More importantly, his advice was to make sure that each executive hire was better at their job than I was, so there was no on the job training while trying to turn things around. He also advised that I make sure I was building a team, not just hiring a bunch of individuals. Lastly, he admonished me to give the new team the space to act, and not try to do all their jobs for them. I was the conductor, and my role was not to play all the instruments. My responsibility was to make sure we all played from the same sheet music and made beautiful music together.

I quickly learned the power of a motivated experienced team. One longterm board member thought it was nuts to hire expensive executives for a company going through the turmoil we faced. Fortunately, the rest of the board was aligned with the need for seasoned talent. What I learned was that hiring smart, skilled leaders early was the fastest path to figuring out how to get the company on track. The cost of the small team of early executives was far less than the tons of capital that would have been wasted trying to figure out the path without their brainpower and experience.

When I arrived at that first CEO gig, the existing team had a pretty consistent view of what the company was trying to do. Unfortunately, it was a “boil the ocean” vision. The company was attempting to build an initial product that spanned a broad range of business processes, and would compete with established public companies that had taken years and hundreds of millions of dollars of capital to build market-leading products. It was a grand vision, but it was far beyond the scope of the team or the available capital. We had to focus on what we could deliver in finite time with the available capital, and we had to pick a market segment where our offering would be clearly differentiated and give us a chance to grow. I heard a presentation by a successful CEO that captured the value of this type of focus. His analogy was a garden hose. When the water is running, if you narrow the opening by putting your thumb over it, the water sprays out faster and further. He said that every time he narrowed the focus of his company, they grew faster and stronger. The learning was that focus was a key to success.

The lesson stuck with me, and I recognized it as a common theme across several of the companies where I was recruited to be the new CEO. Gauging the level of focus became a key element of my diligence when considering CEO opportunities. The recruiting team rarely comes right out and says focus is the issue, so you have to look for it. When probing for why a company is hiring a new CEO, the focus issue usually surfaces in the form of multiple descriptions of the business. Depending upon who you ask, the elevator pitch will be wildly different. The sales executive and the marketing executive are often not aligned in their description of the ideal customer profile (ICP) and the core competitive differentiators, or the CTO describes a product direction that is not aligned with the go to market team. Different board members may express different perceptions of what market the company is chasing, or what success looks like. Once you look for it, you can quickly spot a lack of focus and alignment, and then you have to decide if you will have the tools and the space to fix the situation.

Everyone in a company has to have the same north star and the same definition of what the company does, who they do it for, and what they have to do to succeed. However, in a restart or a pivot, focus requires more than just alignment. It requires the will to stop doing things that are distractions, and eliminate everything that is not in service of the [new] business vision.

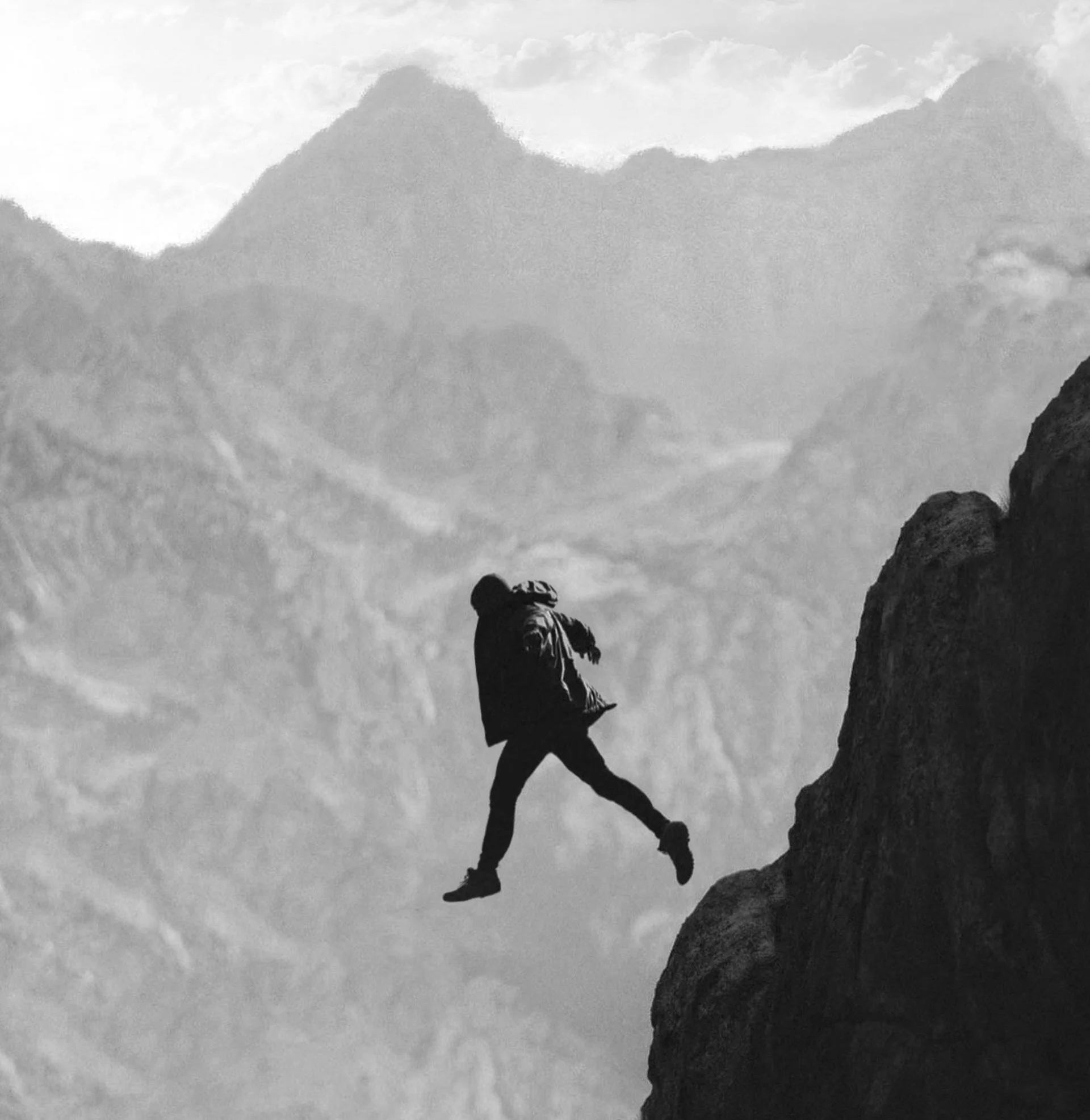

If you are being considered for a CEO position, take these lessons to heart. Figure out why the board is hiring a new CEO, and ensure you are going in with your eyes open. Evaluate the existing team and be prepared to quickly make significant changes. Prioritize focus and ensure that everyone is aligned on the same vision and plan. Never lose site of capital efficiency, and be prepared to quickly make hard personnel decisions to streamline the team and extend the runway. Always be clear with the board and the team about what success looks like. No matter what, take the time to look carefully before you leap.